Haren Pandya murder story When father accused Modi of murder

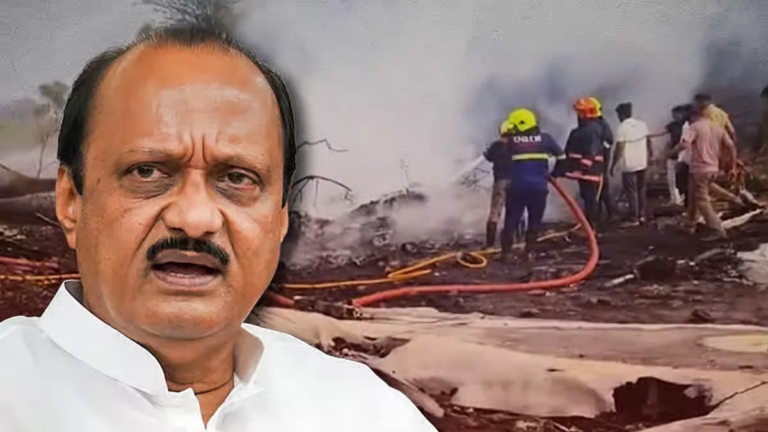

The Supreme Court has convicted 12 people acquitted by the High Court in the murder case of former Gujarat Home Minister Haren Pandya. A bench headed by Justice Arun Mishra delivered the verdict today on petitions filed by the CBI and the Gujarat government. Pandya was murdered on March 26. The CBI claims he was murdered in retaliation for the 2002 communal riots in the state, but Pandya’s father, Vithalbhai Pandya, filed a petition in the Supreme Court openly accusing Modi of murdering his son. In its 2007 verdict, a special court convicted 12 accused and sentenced them to life imprisonment. However, on August 29, 2011, the Gujarat High Court overturned this decision, acquitting all of them. The CBI challenged the High Court’s decision in the Supreme Court in 2012.

Below is an excerpt from “The Uncrowned King: The Rise of Narendra Modi,” published in Caravan in March 2012, which explores the mysteries surrounding Pandya’s murder.

Haren Pandya, a tall and handsome Brahmin with RSS roots and strong media influence, was a fierce political rival of Modi within the Gujarat BJP. The two clashed publicly in 2001. At that time, after being appointed Chief Minister, Modi was looking for a safe seat for his own victory in the Assembly. He wanted to contest the by-election from Pandya’s constituency, Ellisbridge in Ahmedabad. It was a very safe seat for the BJP. But Pandya refused to give up the seat for Modi. A state BJP official recalled Pandya’s statement, “If I am asked to vacate this seat for a young BJP member, I will do it, but not for this man.”

In May 2002, three months after the riots, Pandya secretly gave his statement to an independent inquiry committee headed by Justice VR Krishna Iyer. Modi could not have known what Pandya had said. However, written records show that Modi’s Principal Secretary, PK Mishra, instructed the Director General of the State Intelligence Agency to keep an eye on Pandya, especially on activities related to the inquiry committee. On June 7, 2002, the Director General of the Intelligence Agency wrote in the register, “Dr. PK Mishra has said that there is a suspicion that the Revenue Minister, Mr. Harenbhai Pandya, is involved in the case. He then provided a mobile number, 9824030629, and asked for call details.”

Five days later, on June 12, 2002, another entry in the register reads, “Dr. P.K. Mishra has been informed that the minister who met with the private inquiry commission (Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer) is Mr. Haren Pandya. I also informed him that the matter cannot be put in writing because the issue is very sensitive and the charter of duties given to the State Intelligence Bureau is not linked to the Bombay Police Manual. It has also been revealed that the phone number 9824030629 is Harenbhai Pandya’s mobile number.”

Soon, news reports revealed that a minister in the Modi cabinet had testified before the Iyer Commission, and for the first time, a meeting at Modi’s residence on the day of the train burning revealed that Modi had allegedly ordered senior police and intelligence officials that justice would be delivered in the Godhra case the following day and instructed the police not to interfere with a “Hindu reaction.”

This leak provided Modi with sufficient evidence to file a disciplinary case against Pandya within the BJP. Two months later, Pandya was forced to resign from the cabinet. But Modi didn’t stop there. Elections were scheduled for December 2002 in the state, and Modi seized an opportunity to persuade Pandya to contest the Ellisbridge seat, which Pandya had refused to vacate a year earlier. A person close to the Chief Minister within the BJP told me, “Modi never forgets or forgives. It’s not a good idea for a leader to engage in revenge for so long.”

According to that party official, Pandya went to the hospital to visit Modi. Haren had told Modi, “Don’t pretend to be asleep like a coward. Show me the courage to say ‘no’.”

Modi stripped Pandya of the seat he had represented for 15 years. The BJP and RSS leadership urged him not to do so, but Modi persisted. In late November, RSS leader Madan Das Devi visited Modi at his residence and conveyed the message of RSS chief K.S. Sudarshan, his deputy Mohan Bhagwat, L.K. Advani, and Atal Bihari Vajpayee: stop arguing, don’t create divisions before the elections, and give Pandya his seat back. Devi spoke with Modi late into the night, but Modi remained unmoved. A state party official said, “He (Modi) knew he would be receiving calls from Nagpur (RSS headquarters) and Delhi because he had disobeyed Devi. So, at 3 a.m. that night, he was admitted to Gandhinagar Civil Hospital, citing a strain and fatigue.”

According to that party official, Pandya went to the hospital to meet Modi. Haren told Modi, “Don’t pretend to be asleep like a coward. Have the courage to say ‘no’ to me.” Modi remained unmoved. Finally, RSS and BJP leaders conceded defeat. Modi was released from the hospital two days later, and Pandya’s seat was given to a new leader. In December, he returned to power riding on the wave of communalism arising from Godhra.

Meanwhile, Pandya began meeting every senior BJP and RSS leader from Delhi to Gujarat, telling them that Modi, for his own selfish interests, would destroy both the party and the Sangh. However, those senior BJP leaders who still considered Pandya a key figure in the party decided to bring Pandya to Delhi headquarters as a member of the National Executive or as a party spokesperson. Govardhan Jhadapia told me, “Modi tried to thwart this as well, as Pandya’s move to Delhi could have been detrimental to Modi in the long run.”

Three months later, in March 2003, Pandya received a fax from the party president informing him that he had to come to Delhi. The following day, he was assassinated in Ahmedabad. The Gujarat police and the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) claimed that Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Dubai-based underworld don Dawood Ibrahim had conspired to murder Pandya. Twelve people were arrested and charged with Pandya’s murder. But eight years later, in September 2011, the Gujarat High Court acquitted all the accused and dismissed the entire case. The judge said, “The investigation was completely lax. It was conducted blindly. The investigating officers concerned must be held accountable for their incompetence. This resulted in injustice, massive harassment of many people, and a waste of court time, along with the misuse of public resources.”

Pandya began meeting with every senior BJP and RSS leader from Delhi to Gujarat, claiming that Modi would destroy both the party and the Sangh for his own selfish interests.

Pandya’s father, Vithalbhai, filed a petition in the Supreme Court, openly accusing Modi of his son’s murder. The petition demanded an investigation into the Chief Minister’s role. However, the court dismissed the petition citing a lack of evidence.

RB Sreekumar, who represented the state intelligence apparatus for a year immediately after the riots, told me that he was instructed by the Chief Minister’s Office to constantly provide information on Haren Pandya’s movements and activities.

Zadapaia told me, “I am not saying that Modi had Pandya murdered. But it is also true that within the BJP, if anyone speaks out against Modi, they are eliminated, either politically or physically.”